So, having found our way to the top, or at least, a top, of the Pan-American Highway, how do we go south? The Pan American isn’t a road as such, or a route, it’s more of a concept. So, we might go this way, or that way. South, somehow. It also kept the option of diversions open – if we didn’t actually have a route.

I’d read about the D2D back in February and was mystified by the constant refrain of ‘It’s Not a Rally’. So what was it?

Clearly, seeing as it was an adventure biker event and we were ‘in the area’ we needed to find out. And, it’s definitely south of Prudhoe, and only a weeny diversion away from our route back to Anchorage. Oh, and over the border in Canada. We’d booked in On-line but were aware that they were expecting ‘larger than ever numbers’. The main events took place on the Friday but tickets for the meal, one of the main events, went on sale 12 midday on Thursday. They were sold out by 5 when Nate, a young American from Rhode Island, who shared our camping pitch, tried to buy one.

To be honest it was Fairbanks that we had come from as that was when we turned east and headed for firstly Tok, then Chicken and on to Dawson but we were expected to say Anchorage as nothing else made much sense. If the conversation with our new acquaintances developed we’d explain that we’d flown into Anchorage, bought our bikes there, already done the Dalton and headed over to Dawson when returning from that. Yes, we’d come across the Top of the World road.

The Top of the World road (TOTWR) is precisely that. It rises up to about 1000m for over 100km. It undulates from one pass to another at times sweeping round corners to display fantastic views of the snow topped Mount Sorenson range or tree filled valleys below. It peaks at the little border post where it got to 1280m. On our way back we had been told that caribou were migrating and passing across the road up by the border post. When we arrived one guy checked our documents while the other was clearly scouting the area for caribou.

Our route across TOTWR had had it’s moments. Gid was leading along the paved road, a perfect surface as many highways start. When about 10miles in there was a black patch. A lot of the repairs are in different colours from the original surface being produced from the natural materials nearby – sand, mud, black tarmac (shipped in), grey rock compressed to gravel (if you’re lucky) . Gid’s voice came blasting through the intercom. ‘Shit, shit! That’s deep’. He’d clearly had a wobble. ‘That’s deeep!’ With barely time to stop myself I came to a stand still, in it. Not 6 inches as he’d said but definitely a good 4. Chatting to some bikers later others had clearly been there to with equal tales of surprise and dismay. All happy to laugh about it now it was history.

Other excitement on the TOTWR occurred the following day. One chap exclaimed that he’d had a heck of a time coming across in 6 inches of snow. Mark, a new friend who is part Indian, an avid rider and has lived in Alaska all his life reiterated this saying that he wouldn’t have made it if it hadn’t been for the tracks of the car in front of him. A third person in a car was also dazed by the weather up there. All agreed it was six inches deep. The latter continued that he’d seen 3 or 4 flash fires from the lightening. In our first two days in Dawson we’d got used to the oppressively hot mornings and thunderstorms in the afternoons.

1% of Alaska burns out every year. To give that some perspective, 2% of Alaska is populated. The fires are left to burn out as that is a part of natural regeneration. The old burns down, clears the leaf litter and debris all of which rejuvenates the soil. The roots of the plant Fireweed are fire resistant so it regenerates quickly. It’s also a prolific seed producer which in turn brings in the birds, squirrels etc. And off it goes again.

Whilst all was clear for our way back to Anchorage, where we were getting the bikes serviced, it wasn’t the case one week later when we returned to Tok, the launch point for the TOTWR. Revisiting Eagles Claw campsite, a bikers campsite at Tok, the chatter was all about the road being closed between Dawson and the more southerly town of Whitehorse, because of forest fires. It had been closed for a couple of days and we were strongly advised not to go that way. The following morning the road closure was confirmed by the Yukon news station. Several days later it was still closed with one or two trips being lead with a pilot car, as a lady hoping to make the journey was telling me.

So, the D2D. Bikes were arriving from all points. The widest possible range of old and new adventure bikes, and a few brave cruisers (Hi Behr, hope the 34-year-old Electraglide made it home to Germany!). The poker run turned out to be – in the continuing good weather – an enjoyable 60 mile or so loop along local dirt roads, stopping at places of interest to draw a card. When we looked a bit nervous on the surface in places (read – slow), Nate was good enough to stick with us as others whizzed past. In the end, only one little bit felt challenging, but we’re definitely slow. The ride looped back to Dawson for a jolly good natter with other bikers at the steak feast prepared by Dawson Fire Department (proceeds to local charities). Then outside for the biker games, which definitely planted ideas for our RoSPA SMART training team back home. Mark appeared again here, as a bit of a star (opening the slow races – on his Ducati). And, as well as the (informally) organised events, an awful lot of chinwagging, and I suspect, beer too.

We hadn’t twigged before we got there, but Dawson City is the famous historic town at the centre of the 1898 Klondike gold rush. Well, it wasn’t historic then, just a gravel bank that the local Athabaskan Indians appreciated as a summer camp. They withdrew as swarms of smelly prospectors turned up by boat, and built a camp. Enterprising non-prospectors quickly built a town. After the gold was gone, it quieted down a lot, and now is reinvented as a living memorial to the gold rush (ahem, tourist town), with still a bit of a supply centre for the remaining local miners. Many of the buildings have stood still although some explained that many decades of the permafrost melting and re-freezing beneath the buildings had shifted the foundations severely. Now some are decidedly wonky.

That big grey thing is a gold dredger. These gigantic barges were winched through the river bed, banks, and shoals, washing gold out of the gravel. A reminder that for all the romance of “panning for gold”, the early 20th century was an industrial age.

Dawson City is at the confluence of the Klondike and the bigger Yukon, and the river boats came downriver from Whitehorse. Sourced with snow melt in BC, Canada, just kilometres away from the Pacific south-west coast of Alaska it heads north and inland and has carved a route out all the way to near the Bering Strait 1,980 miles away. The fast flowing water that passed our camp site was thick with silt. It’s hard to imagine it frozen solid throughout the winter. Sufficiently so that it will take the weight of fully laden trucks as clearly the 24hr ferry can’t operate. During the months of non-drivable ice, the part of the city over the river is isolated.

Photographs recorded the harsh conditions and ill-prepared prospectors. The latter was reiterated throughout the graveyard where tomb stones displayed the names of failed young hopefuls at the tender ages of 26 / 27. The paddle boat graveyard was another vivid record of a by-gone days although the structures to lower the boats into the water still existed, as well as one hauled-out old timer to tour.

The Dalton Highway especially is billed as long distances between any services, but other, more workaday routes in these parts still strain the endurance of riders and, especially, motorcycle fuel tanks. The main road (really, it is!) from Anchorage/Wasilla/Palmer to Tok, had my bike 60 miles into reserve before the well-named Eureka Lodge around halfway provided fuel, coffee (25 cents!), food, and more bikers. The Top of the World road also involved a bit of vapour running, and those roads weren’t the only ones. Gid’s Himalayan seems to have a rather panicky fuel gauge, but also it seems to be thirstier than Clare’s. Maybe it’s just more loaded or bulky. The big bags on the front tank bars do provide a lot of weather protection, though. 60 miles into reserve (as in, the dashboard flashes, there’s no tap), gives a total range of something over 200 miles (haven’t actually conked out yet), and then there’s 2 gallons (~8 litres) in the can on the back. Clare’s front tanks total 6 litres, so we probably both have around 300 mile range.

On these long connecting roads, there will be a few small communities along the way but nothing more than a few scattered dwellings that are in a full tank distance. The sheer distance between places is remarkable for a mere Brit. That’s not just Alaska – now we’ve moved into the Yukon, although the scenery and signage differs, the immense distances and rare communities continue.

From Wikipedia:

- Alaska – 665,384 square miles, population ~733,000 (nearly a square mile each), the main part is roughly 1,500 miles long and wide.

- Yukon – 186,272 square miles, population ~45,000 (about 4 square miles each), around 1,000 miles along the two short edges.

- Great Britain – 80,823 square miles, population ~66,000,000 (about 1/743rd of a square mile each), 600 x 300 miles.

Highways are frequently numbered and often named. The longer ones, unless they really are major arteries are typically some part dirt road. Even on metalled sections, ‘repairs’ are frequently areas of gravel spread across the road sometimes for 100m or so and have been known to cover several miles. The weather isn’t friendly to roads. Spring melt floods regularly wash away anything in their path, so some parts simply aren’t worth making up nicely as they’re re-laid annually. And often there’s frost heave or problems with permafrost – many roads are basically millions of pounds of gravel laid onto the permafrost, again, it maybe isn’t worth making a nice finish. But gravel roads can’t take much traffic before they corrugate, and the dust is a major hazard which prevents high density/high speed traffic. So, dirt roads rule in the sticks. They’re a lot better than Latvian ones though, loose tomato sized rock surface and pretty tight bends were frequent there.

The Dalton or the Dempster?

Sitting in our armchairs at home we’d barely heard of the Dempster, not until it was featured in Motorcycle News just the week before we flew out. A pair of tour leaders exclaimed that it had been on their bucket list for a while and they’d just achieved it. That was our first awakening to it’s existence as a biker road. Out here it’s definitely the one to do. ‘You’ve got to do the Dempster! The Dalton just dumps you in an oil field,’ one enthusiast was trying to persuade me.

Although some of the resident bikers in Anchorage we’d spoken to have never done the Dalton and don’t intend to, because of the difficulties in riding it, it’s clearly yesterday’s challenge. As we’d continued on our travels around Alaska bikers told of their Dempster ordeals.

‘Six inches of thick mud all the way’, one grave looking soul who’d just finished it told us.

’80 kph is the only way to crack it. That way you just fly over the pea gravel.’

Wallowing around in the Canadian gravel, some pea sized, some egg sized, which, all agreed was dug up from the river bed and smooth felt like walking on marbles, as opposed to the Alaskan mountain gravel that is crushed and jams together when pressure is applied, was not a great option.

‘It took a while of wallowing to even think of trying it but it worked!’ Richard exclaimed still pumped up with riding at 80Kph across the gravel and beaming from the success. Luckily our 24hp bikes probably won ‘t get to 50mph in deep gravel (who knows?). What a relief.

So, all these dirt roads and wobbly moments – what was the damage? Luckily, we haven’t yet had a spill on these Himalayans. That compares to 3.5 drops of our UK Himalayans, in few miles. But Gid’s bike had been on the deck twice by now. Once, after dismounting in a highway rest area, on a seemingly well chosen surface, the bike decided to lie down. BANG went the airbag vest as the leash pulled out, leaving Gid standing bemused and squashed beside it. No damage apart from a £25 airbag cartridge. The other time, in Safeways’ car park, after shopping, Gid pulled a little on a loading strap, and the bike just toppled. The strap was on the left, and the bike toppled right. It’s a known defect of the Himalayan 411 that, designed partly in the UK, and otherwise Indian, it prefers to be parked on the left hand side of the road’s camber. Especially when loaded. In other words, the side-stand is too darn long! Clare’s UK 2018 bike got an adjustable, but driving on the left, Gid’s UK 2023 seemed to indicate the defect was fixed. Not so. And the forums confirmed it. A solution was needed, we can’t carry on crossing the road to park when there’s population.

We’d headed back into Anchorage for the bike’s 3,300 mile service. We figured it best to have this done at the shop because they know what noises a Himalayan should make, and it might help with any future warranty issues. We also picked up our proper Alaskan plates and title documents.

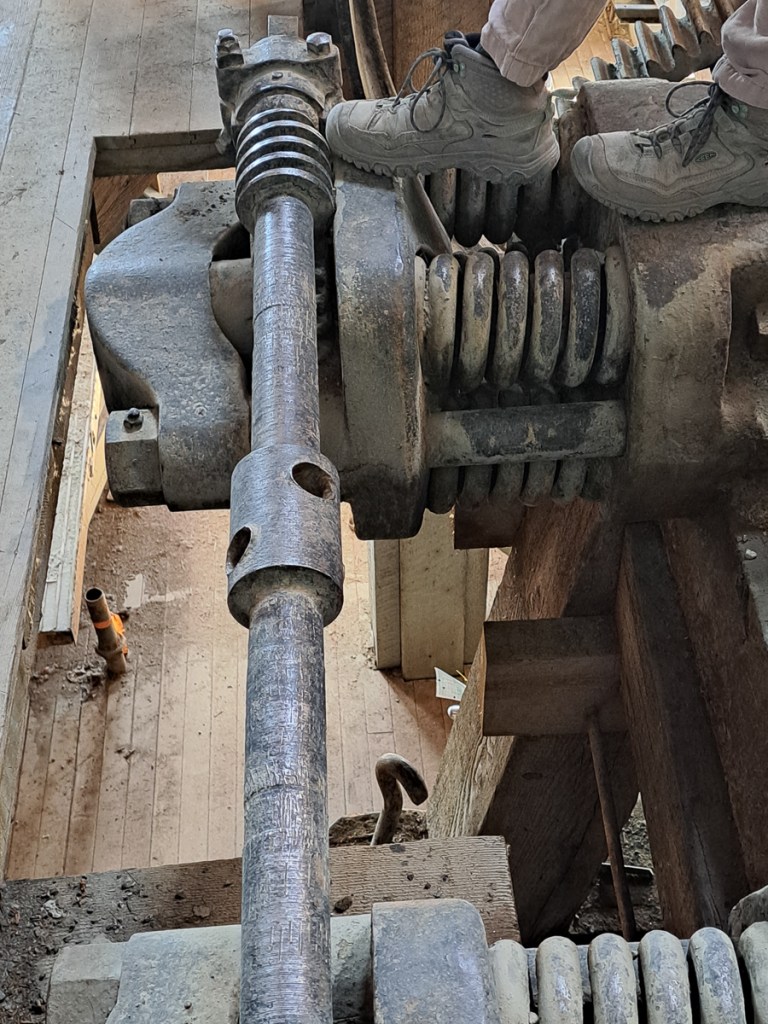

Tim at Wasilla, having helped us previously when setting up the bikes, had generously offered to shorten our side-stands. We’d had some delays in Anchorage. Getting lost on the way out didn’t help. But when we finally arrived at Tim’s another mate had turned up with an unexpected extra elderly BMW to salvage. Didn’t know BMW did orange bikes. Inexorably, our offer to treat Tim and his wife to a feed was defeated by the clock. Heather, Tim’s wife, generously fed us! A sheepskin seat cover also came our way. What a lovely generous chap! Clearly he’ll need to visit us in the UK.

A couple of people had mentioned McCarthy while we at the Eagles Claw. ‘The place is a copper mine museum and it’s about 60mi on a dirt road but that’s ok once you pass the fishing bridge,’ Stranded Strommer Steven, waiting for parts for his broken down V-Strom had told us. ‘And you can bike across the footbridge to get there. Cars can’t but bikes can’. That clinched it. I had visions of a suspended rope walk bridge that I could cross on a motorbike. It was straight out of some of the videos I’d watched of Vietnamese ladies, infants on their backs, careering up the side of mountains on heavily loaded 125s. Now I had the chance of crossing something in dare-devil fashion. Nervous anticipation was quick to set in.

The road up there was no problem. It was somewhat corrugated but corrugation, mud and gravel in moderate doses were no problem now. Then there was the fishing bridge. Smooth wide concrete across a braided gravelly river. The word was out, the salmon were coming in. There was an air of excitement. It was evening and pickups were arriving regularly, parking on the gravel banks and everywhere else. The river was shared by the rod guys, the wader guys dipping nets wielded at the end of 20ft poles and the bald eagles over head. Spectators watched along the road side. It was definitely a community event, although we didn’t see so much success. After the fishing bridge there was a worrying road sign, clearly designed to deter traffic from proceeding, but actually apart from the road being a bit narrower than before, it was nothing to worry about.

The village of McCarthy, 1km after the narrow but extremely solid metal footbridge we had ridden over, offered tourist facilities and a general store with the usual frustrating mix of things one doesn’t really want, Alaska’s slowest Wi-Fi, and cheapest ISO propane bottles. We rode on to Kennecott where we joined a Kennicot mine tour (Both spelt correctly). Fascinating: Back in the early 20th century it made a ton of money for the owners, and was abandoned in 1938 when the copper ran out. Keen to do some walking we were back the next day, plagued by mozzies at first as we walked along the dingy old wagon road, and on past the mill to visit the glacier. Our first real walk since we got here. And, Ting-a-ling, we remembered the bear bells! Knackered, we dined out that night – luxury. Actually, Alaskan groceries are so expensive that cheaper eat out options are pretty competitive.

From McCarthy (Hwy 10), we headed back to the main road, but this time turned left, heading south-east: towards Canada on the Alaskan Highway. Although Alaska is huge, it has few highways – we probably had traversed most of the metalled ones outside of cities.

It was, rather tidily, July 1st when we crossed the border. Clare’s “tiny bear spray” turned out to be, formally, “pepper spray”, ie for defence against humans not bears, not allowed in Canada, so she had to fill in a form and surrender it. While she did that, I idled round the bikes, and found another missing bolt (running total 3 lost plus 1 tie-wrap, and 2 loose). Easily fixed, but we need to watch our stock, despite commercial and Tim’s replenishments. Well, as we head into Canada, it’s only 2,000 miles until the bikes need another service (perhaps done ourselves this time), and the rear tyres, especially Clare’s, look pretty worn (after only 5,000 and 4,000 miles respectively). So we were already thinking of a service stop.

Our month in Alaska is done. The overwhelming impressions are: Space, sun (!), empty dirt highways, moose at any point, friendly helpful folks – and a lot of motorcycles.