We’d spent the previous afternoon filling in the forms at the campsite. Gid’s android translated the info into English. Mine didn’t. I felt as though I was signing my life away with a blindfold over my eyes. He was feeling challenged with his own form and didn’t need me constantly quizzing him. We finally got there. Paid up, two forms. Copies of this, copies of that. But one of them said we needed a paper copy and please arrive at the border with it. We were crossing the border on a Sunday and suddenly we needed a paper copy.

On the way out of our Palomar campsite we’d called into the local convenience store. The part time lady cheerfully said she’d ask the manager for a print as they did have a printer. It all seemed quite hopeful. The manageress arrived flushed and in a considerable flap. ‘I do wish you hadn’t offered to do this,’ she admonished her assistant. Despite three heads trying to solve the problems it was not going to happen – passwords, signals, connections – the list goes on.

Gid was keen to try the few random shops we passed. I was more, ‘Of ‘cos they’ll let us in. Are they really going to send umpteen tourists away?’ One more failed effort just before the Mexican border left us with no option. We progressed forwards. It all seemed very relaxed. There were a few officers there in uniform but they just waved us through. Gid exploded. ‘We can’t just go through. We need our paperwork stamped and the bikes need to be registered.’ He conveyed this to one guy who casually pointed to the office at the side and told us to go through the barrier and come back to do the paper work!

The Mexican immigration office was to the right on a one-way street. With no access to it we had to park further down the road and walk back. The señor in the office was very patient as we tried to locate, from among the umpteen forms we’d saved, the ones that he wanted. We emailed them to him so that he could print them out. Stamped and dated off we went. The vehicle importation was equally trouble free once we’d sorted out which paperwork equated to which bike and whose it was. Our recently hard-won, but very elementary Spanish hadn’t really been challenged, but it had had a little outing.

In. Now we needed some Pesos. Going down the main drag I spotted an ATM sign. We pulled in behind a car. Gid jumped off his bike and in he went. Moments later un hombre policia appeared pen in hand opening the pages in his ticket book. He pointed to the writing on the side of the kerb and said what must have been, ‘No Parking’.

‘Un momento, Un momento,’ I cried, calling to Gid through the intercom that he was about to get a parking ticket.

‘I’ve just put my card in, I can’t come now,’ he anxiously replied.

The policia was gesticulating that Gid’s bike needed be to moved. I indicated that I would move it. But of course as I swapped bikes mine was now illegally parked. I was trying to wiggle Gid’s bike round mine when Gid reappeared. Thankfully the policia seemed to despair of this comedy act and walked away. Two bikes two riders, money, we were off.

As we set off down the road Gid informed me that a high proportion of the population have never taken a test. Pay a little extra and the licence was yours is what most Mexicans did. Somehow I was sensing that and the signage wasn’t as clear as we’d got used to either. There were stop signs used in the same way as in the US but the accompanying stop line had been erased – some of the signs had suffered over the decades of time. I ploughed straight through one. Thankfully no one was coming. Later we learnt that irrespective of red lights, Alto signs and what ever, ‘Get eye contact!’ before progressing, that’s the important thing. Things seem a little “loose” compared to the UK, Spain or USA, but it works on civility yet is not remotely in an Indian or Indonesian league.

Further down the road I was overtaken on the hard shoulder. A car just came careering past me on the inside. Wow! What was that? The next half hour was a sharp learning curve. The hard shoulder albeit much narrower than the road lane was regularly used to over take. One vehicle straddled the solid white line that demarked the hard shoulder while the overtaking vehicle straddled the central solid yellow line. All sorted then. One good thing was that as the hard shoulder served as a lane, of sorts, it wasn’t full of debris. The crap was piled high in the pull outs and off the side of the road. No $1000 fine here for littering.

Another surprise was the trucks passing along through the towns and along the highways with armed soldiers masked and in full uniform standing in the back. Regular check points along the roads also told of the extent of the drugs problem in Mexico, a lot of it driven by the trade over the border in the USA. The nearest we got to being searched was one bored pair of young military guys asking where we had come from and where we were going. Other vehicles, mostly northbound, had numerous inspectors with torches pawing all over their trucks. The bigger the vehicle the more extensive the search. We settled into the new regime. The road to Ensenada passed through a scenic wine making area, and wasn’t heavily trafficked – a great introduction once we’d worked out the hard shoulder plan.

Ensanada was our first destination, for very prosaic reasons. But it was a joy to visit. The internet-booked motel was just fine, and after months in the western USA and Canada we could again wander around a town. While none of the pavements were consistently flat it had a centre we could amble through enjoying the atmosphere. Gid could have stayed a few more days, but after all the delays I was keen to get on. The plan was to travel the length of the Baja peninsular, then ferry across to the mainland. Interestingly, it was two weeks before the famous Baja 1000 desert race. We decided not to enter.

We’ve visited Spain a number of times and the similarities here were stark. In some towns with buildings set back from the road, many things were broken down or in need of repair with the occasional thing half built while others had large murals and were brightly painted with bougainvillea adorning the walls. Whereas the western USA has almost everything in town concreted over, in the pueblos the road had a wide apron of dust – of course, everything was coated in it unless it moved.

We’ve travelled fairly extensively across the globe, and it was a pleasure to see again local, improvised, low key services along the road. Home made as well as printed signs are common, and as Baja California is both very sparsely populated, and not highly developed, sometimes we needed to see that “man with a can” gas stop, or the little stall selling burritos (we hadn’t even been entirely sure what a burrito was). And every café had a “wifi” sign – the wifi may well have been the most reliable service. There were many “proper” gas stations, but interspersed with can men whom we really needed at least once pricey though he seemed. Very sugary pop is also always available, more difficult is avoiding it!

Another change – to us – is an expected one. In the USA we tended to avoid the trafficked and expensive megopolises, and skip from scenic park to scenic park, camping. In the less developed parts of the world, there are fewer campsites, debatably less safe, and our pounds go a lot further. So we tend to reverse the pattern and skip between cheap hotels in towns. Cheap hotels here can be jolly nice, usually best not booked through a big website – local rates are cheaper. El Hotel Frances was a memorable 19th century historic building, in rather mid-western style (but of probably tropical hardwood), but most are pretty new, Hispanically concrete. None has yet approached in cost the San Diego campsite!

We still felt very wary of much adventure in Mexico and there’s only one main road down through the Baja peninsula which was generally ok, two lanes, little traffic, and relatively few slow bits through pueblos. Occasionally it was a pristine new surface but at times a pitted pot-holed mess – no worse than our home town in the UK, but that’s not a 60mph road. On our Himalayans we didn’t need to lose much speed to plough through whatever the road surface threw at us. Along the grotty sections we even overtook some cars and trucks. We passed a road repair team on a couple of occasions. It was a truck loaded with tarmac and some spades. The truck stopped. Out jumped the team. One filled the hole, another raked it flat while a third flagged the approaching traffic. All sorted. Move on. They had their work cut out! More dangerous than the overtaking, and the potholes, was probably the occasional livestock, rare in the first place, that had gotten out of the fenced ranches and now munched at the roadside.

But plenty of the roadside was also lovely to look at, and especially in the north, quite curvy with fabulous views.

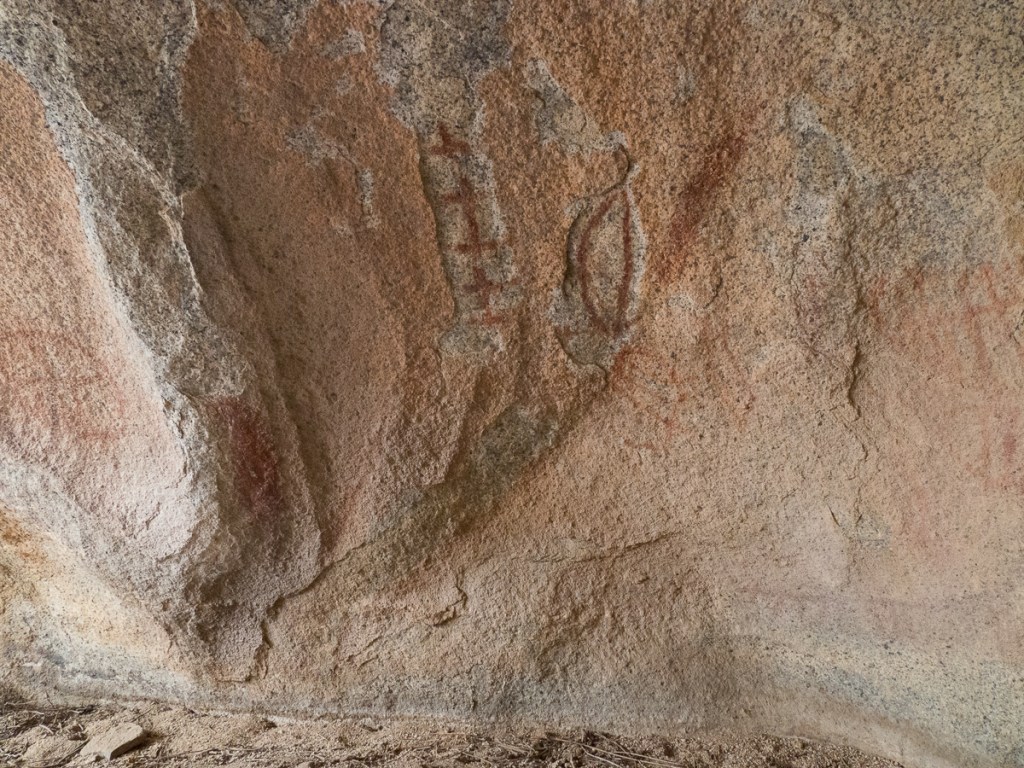

The country side we passed through changed from sparsely covered desert to a rich environment with many desert plants thriving. Despite my resolution to not camp in Mexico on the grounds of personal safety we did camp at Cataviña. We’d just passed a police station next to a deserted motel when we came across a small community: a campsite with two motorbikes and a tent inside a perimeter fence, opposite a taco shack and a fuel stop. Encouraged by the gated entrance and bikers already camping we went in and were enthusiastically greeted. We were staying then. Alexandros spoke reasonable English and encouraged our efforts in Spanish. He’d also done the southern half of our planned trip and gave us the book he’d written pointing out the pages that recorded his crossing of the Darien gap. ‘Three weeks for the bikes,’ he said. ‘Three hours by plane for us.’ We spent a fabulous evening sharing tales. A surprise bonus was the campsite’s tour of the desert by truck to see the painted caves just up the road and off in the desert.

So, we’re off! ¡Vamos! Well, now we stopped in the lovely resort of La Paz, there is the ferry terminal, but it’s so nice we’ll pause awhile.