After Mexico, we were lulled into a false sense of security by the smoothish roads in Belize. Except for the road approaching the Guatemalan border. That was full of pot holes, dirt, gravel and was generally broken up in places. At the border the bikes, as usual, demanded more time than we did – numbers had to be checked against documentation- registration and vehicle title, photocopies of driving licences provided, wheels and underneath framework sprayed. The whole process took 2 1/2 hours with the guidance of a local helper, who magically appeared at our sides. Strictly speaking, his services were unnecessary, but he knew where everything was, and probably saved us 30 minutes. No specific fee was solicited, I think we tipped him 50 Quetzals – about £5 – probably too much.

Then – we were back into the bumpy ole Mexican style roads.

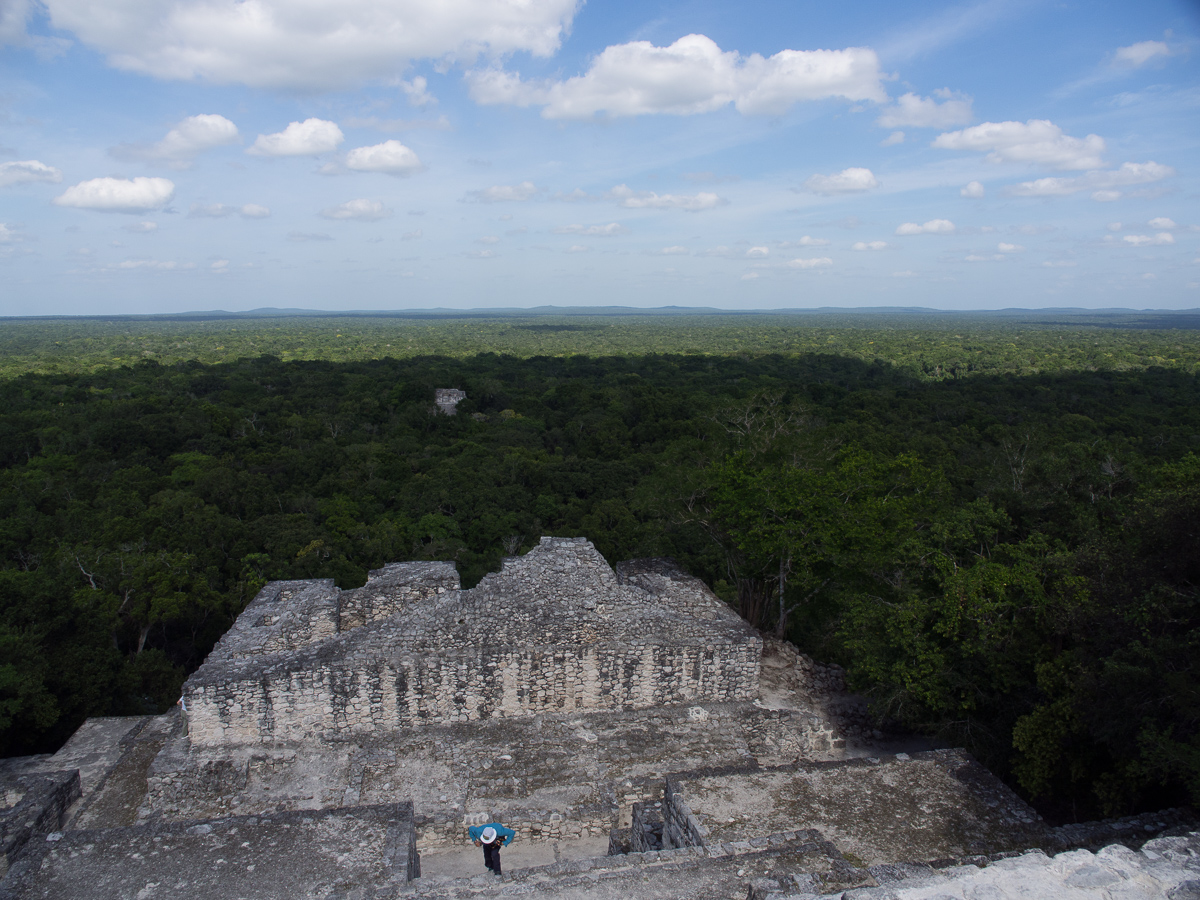

Initially we stayed on the main road into Guatemala. The decision was easy as it is the direct route to one of Guatemala’s key tourist attractions – Tikal, which we were keen to visit. After that we went a bit more freestyle.

Until we left Mexico, we had had quite good navigation. My Garmin Zumo XT was the mainstay, and Gid’s cradled and powered Android phone with OSMAnd was backup and a second voice. Both systems often came up with different routes and both maps had a different interpretation of ‘no dirt roads’/’no 4×4 roads’ and other criteria. The Garmin also scores in crowded areas because it verbalises the instructions. ‘Turn right at the traffic lights’ is useful in crowded unfamiliar areas. Although maddeningly, it cuts off the intercom not only while it does so, but for many seconds before and after just at the point when we are trying to discuss the intricacies of our route. OSMAnd verbalises too, but it’s instructions (or mapping) are poor, and utterly useless around slip roads, which it can only display in very limited circumstances.

As a back-up and for planning we always have a paper map, old farts that we are.

But as soon as we left Mexico, Garmin’s North America mapping finished, leaving a blank screen. Occasionally it did show a road but we wouldn’t be on it. It wasn’t a big problem in Belize because it is a small country with relatively few roads. The small scale free tourist map did just fine, although absent from it were the new bypasses of some of the larger towns such as Orange Walk.

Gideon: In Belize we hit quite a bit of rain, so the cradled Android phone was pretty useless. The charging arrangements are not waterproof, and it can’t run all day without power. The Samsung A series phone is nominally waterproof, but water got into the camera, and it now often won’t focus properly. It’s not just waterproofing as such – a phone touchscreen can’t reliably distinguish raindrops from fingerprints. Clare’s Garmin is a totally waterproof device wired into the bike’s main battery and has an outdoors touchscreen (and big buttons), so it isn’t fazed by riding in wet. Thankfully, we’ve just discovered, I can at least download the free Open Street Maps onto the Garmin so we have reliable navigation in rain but now it’s the same data as Gid’s phone, so we lose the useful combination of different mapping systems.

Why not use Google Maps? Well, the basic reason is that one pretty much needs to be online, and in the trickier or remoter areas there’s frequently no signal. Also our IT incompetence and my strange priorities and meanness means that we don’t have a good, mountable, phone which will work on American cellular frequencies. The upside of this is that if some hood does nick one of our phones, we can giggle about their experiences when they try to sell or use it. Clare’s is over a decade old, and its “new” battery holds charge for, well, several hours – if it’s turned off. Mine doesn’t work on American networks, and the camera focus is broken, and has either an expired Latvian SIM, or an expired USA SIM – ideal to leave on the bike.

Speaking of navigation, for those family members unfamiliar with Guatemala (Map here), we entered the country in the little inhabited, jungly, north. Flores is a scenic village on an island, in a lake, in the middle, and Quetzaltenango, Lago Antitlan, Antigua and Cuidad de Guatemala run from west to east along the spine of volcanoes that run about 75km north of the Pacific coast. For the first time on our trip, we actually rode on “the” Pan American. The carreterre was named on signs. It runs along the north slope of the volcanoes, from Mexico in the NW, out to El Salvador/Honduras in the SE. Most of Guatemala’s 18m population is in this southern part of the country. In retrospect, it’s no surprise that the roads in the north are, err, quite adventurous.

Clare: Heading from Flores down to Xela (Quetzaltenango) was quite eventful. Gid had programmed in the destination and was informed that the 90 odd miles would take seven hours. Cursing the lack of information on the map of Guatemala he assumed that the time required for the trip reflected the mountainous area we were coming into and was quite relieved when he realised he’d set the transport option to ‘boat’. Boat wasn’t so far out. We did wind our way up and down the mountains, the roads were quite little. It was at the bottom of one of them that our road ended at the river. Approaching the tail end of the queue of cars Gid was on my left. I could see the small wooden boat almost full of motorcycles starting to pull away from the shore whilst Gid was looking at the large nearly fully loaded car ferry. ‘We can make it!’ he was saying, urging me forwards. Noticing that the little wooden boat was indeed returning for us I gingerly progressed down the muddy sloping bank none too sure about the prospect of boarding it. Gid, still focused on the car ferry, hadn’t a clue where I was going. ‘The ferry,’ he was saying ,’the ferry!’. Well if that’s what you call it I’m on my way I thought. I stopped 2/3 of the way down none too sure about what I was committing to. Gid by now could see the little wooden boat and was horrified with where I was heading. ‘The Car Ferry!’ he shouted. Too late, half way down a wet muddy bank I couldn’t turn round now. I decided I was going for it, took a deep breath and was internalising ‘Give it some throttle over the metal grid, over the lip at the edge of the boat, then brake hard before I hit everyone else.’ The theory was great. I managed it. I shuffled forward to make room for Gid knowing he would follow. Bless him, he did. The crossing was brief, but about halfway across one of us realised that the boat – floored with loose, gappy, planks – only had a ramp at one end. Sure enough, the local riders, clad in jeans and tees, had all swivelled their 100Kg motos around on the side stand. Oh shit! A loaded Him weighs about 250Kg. Everyone was delayed while we sweated our steeds through 25-point turns wearing All-The-Gear-All-The-Time.

Later that day we still had to reach a sensible place to stop as our actual destination was several hours away. We made the decision to find somewhere to stop at about 3 pm. Plenty of time. The first town we entered didn’t have accommodation with off road parking and it was still early so on we went. By 5:30, and aware that it would be getting dark soon, we were still looking. Just a bit further up the road towards the next town Gid was saying. It sounded promising but an unexpected diversion we were meant to take was blocked off. In amongst a deluge of swearing Gid shouted “next left”.

‘Have you seen it! You are kidding!’ I replied.

‘Well, it’s got to be one of these, it’s a short cut back to the main road,’ he said, urging me on.

We took next left. From the start it was a pretty rough narrow lane. ‘It’s no worse than Mill Lane,’ he assured me, the rough track to our home in the UK. After 10 mins of up and down past houses and homesteads we were about to reach the main road Gid declared. Fast acceleration got us up the next sharp incline but no-one in their wildest dreams could call it a main road. We had an ariel view over the valley of widely spread dirt lanes interspersed with houses and smallholdings. The stone strewn, rutted dirt track under our wheels continued who knew where. We turned back.

Thankfully, approaching the nearest town from the other direction enabled us to see a hotel sign. It had a gated entrance, always a requirement. In we went.

The following morning we had another look at the map and navigation. There didn’t seem to be any reason why OSMAnd had directed us off the main road. The “shortcut” looked ludicrous when we could sit and study it. Gid figured that perhaps the OSM data for the main road had a tiny break in it, or 5 metres of dirt road, so OSMAnd would not route it unless it was allowed to use all the dirt roads (we’ve seen this before, but then the Garmin was working and happy to make sensible compromises). Determined to stay on the main road we set off. It wasn’t long before the surface deteriorated. We had patches of broken road, stretches of gravel and the odd bit of sand. So much so that when we came to a dirt road that was a legitimate short cut we decided to take it. It started off fine and generally was but had some interesting sections of hairpins, gravel, rivulets and ruts. We made our way down the mountain side across the bridge and up the other side. Nearing the top we thought we had made it and were quite surprised to see the road ahead blocked. A policeman directed us to his left waving his arm in a snake like fashion to show the direction of the road. A dust trail to his left confirmed the direction of the road and that other road users were on it. It was clearly a single track lane with very poor visibility because of the dust flying up. We set off not knowing how long this diversion was or what traffic we might meet.

We reached a steep hill and approached it behind a 125 that had come careering past. It whizzed up. Dust flying. Gid was right behind it. ‘1st gear, 1st gear, ‘ he was calling back to me. ‘And plenty of throttle.’ No one was getting up that hill without plenty of throttle but what was about to come down? Thankfully, shortly afterwards we reached to end of the diversion. The poorly surfaced concrete road seemed awesome.

Heading further south in Guatemala we were back on surfaced roads. Belize had offered a respite from Mexico’s endless tupes/speed bumps, but in Guatemala they were back with vengeance. Some are quite brutal – Gid has scraped his bash guard on a number of occasions, and now takes most of them standing.

On the other hand, bikes are a lot quicker across them than anything with three wheels or more. Both us and the local riders get a lot of (slow) overtakes in at the speed bumps especially when they’re one of the few places the chicken buses slow down. Oddly enough, later, in Cuidad de Guatemala where there aren’t speed bumps, we’ve seen quite a few Porsches (I mean real ones, not repackaged Touaregs) – they and similar low vehicles must be pretty much confined in city limits – odd.

Reaching our destination, Xela, was also interesting riding as in the old town where we were staying it has a great grid of calles and avenidas cobbled with pretty much random rocks. They’re ok at speed, but stuck behind crawling traffic, the bike’s front wheel swerves all over the place. As the streets are so narrow, it’s an irregular grid of one ways, making navigation tricky, and distances much longer than the map suggests.

It must have been around this time that we started seeing tuktuks. I don’t think there’s a factory nearby, I think they’re all imported from India. For some reason, they’re almost all red. They seem to thrive in mountain villages, or pueblos & cuidades with tiny streets. They’re geared to labour up any mountainside, but with only half the Himalayan’s engine, and six people aboard, boy, they can be slow. They must be alarming to drive around downhill hairpins, too.

To reach San Pedro on Lago Aititlan from Xela, we turned south-east, aligning us with Guatemala’s volcanic spine. So we encountered the actual Pan American Carretera. Woohooohoo! Here, it’s a mostly well-surfaced dual carriageway. Not, normally, the Himalayan’s favourite domain. But this road corkscrews its way up, down and around the volcanic slopes, and almost all the wiggles are blind, so few folk dare exceed 50mph/80kph even if their vehicle can do so (and many here can’t). The Himis were fine, although a little more overtaking ooomph, or even a lot more, would be appreciated. Still, we tried to exercise restraint: Altogether now: “Drive at a speed that will allow you to stop well within the distance you can see to be clear” (UK HC Rule 126).

Occasionally we’d be passed, sometimes by a chicken bus – these often belching clouds of black muck from a primitive, or maladjusted (depending on age) diesel engine. USA school buses are tightly regulated, and it seems have to be retired at quite modest mileages and ages. So, like a fair few human retirees, they head south in fleets, and live to a great old age as chicken buses. Often these are brightly decorated, usually they have powerful horns, to blast traffic and alert potential customers. The drivers are not necessarily the most cautious and safety aware of señores, although not remotely in the homicidally obnoxious league of their Indian and Indonesian colleagues (or Aussie truck drivers). So they do tend to hurtle around the bends – after all, the driver saw no obstacle there 2 hours ago, so there can’t be one now, can there? We saw the aftermath of one apparent head-on between a bus and something smaller… the bus seemed to be facing the wrong way at that point. Looked like it’d need a new cab.

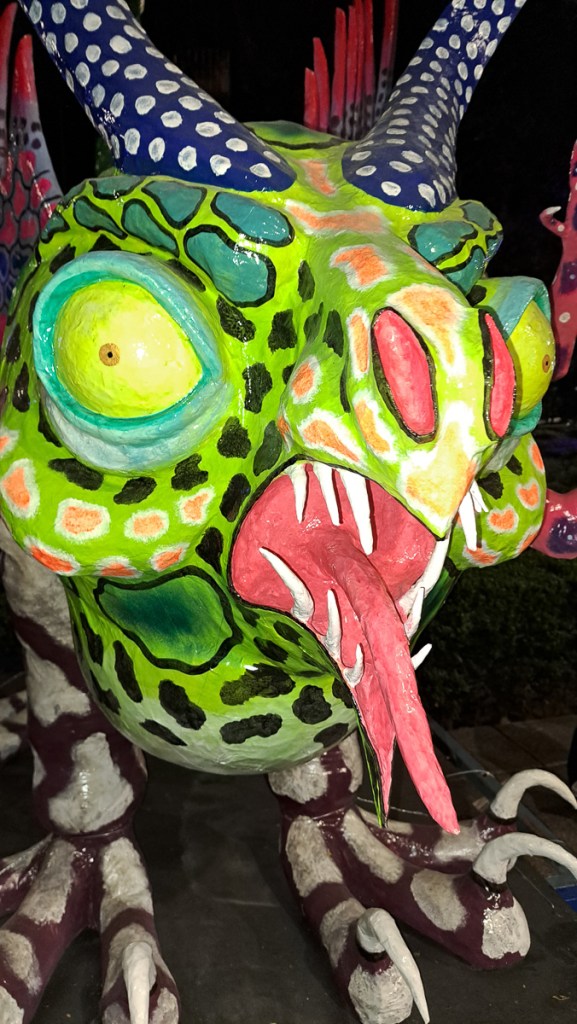

Finally, a few snaps of curios encountered on the roads. If you’re into 70s/80s car and truck nostalgia, or radically optimised loading, there’s plenty to entertain on Guatemala’s roads.

Postscript: Sadly, a week after posting this, 55 people were killed in Guatemala when a chicken bus crashed, and a few days before that, nearly as many died in a bus accident in Mexico. On our way back from our volcano hike at Antigua, our shuttle passed a fatal motorcycle accident, the poor fellow still lying in the middle of the road.