Panama was to be a means to an end. We had to enter it because that is where we will fly or sail past the stretch of land known as the Darien Gap. It has been crossed with motorbike – not by motorbike. At an Overland event back in 2018 we attended a talk by a chap who had taken his bike across the Darien Gap. He had had his bike strapped to a float/pontoon and a number of ‘gerkers’ to assist with getting the bike through the jungle, across the swamps and passed the bandits. Not for us!

Neither is the more attractive route taken by Itchy Boots, an infamous motorbike blogger, when her bike was lashed onto a small fishing boat as the family sailed her across in what she has described as a ‘nerve wracking trip’. These sort of crossings that visited the islands on the way are increasingly clamped down on by the authorities. A ferry frequently referred to is alas only found nowadays in the ether. Our choice is air freight or container ship. Three days, or three weeks. Expensive, or cheap – well that’s before you add the cost of the storage before and after the actual shipping at extortionate prices per day. Then there’s the need to meet at a time that’s convenient to all the people with something in your container as it won’t be opened until all are present. The actual cost is also dependent on what else it is possible to get in the crate after our two bikes. We’ll fly them across! As far as we can tell, it isn’t even significantly worse for emissions, although clear info on that is hard to come by.

So, is Panama merely a route to the airport? Heck no, there’s loads to see here and it’s pretty accessible – except for the canal zone which is very extensive, definitely private property and well, if politely, guarded.

The Rio Sereno border crossing is well named. A laid back sleepyville, with a helpful biking janitor, a slow process, but low hassle for a border. Thirty minutes into Panama we were in the comfort of Helen and Scoop’s home. Helen, an ADVRider ‘Tent Space’ member, was kind enough to put us up for a couple of days while we found our feet and got to see some of the local attractions. This is the second time on our trip that we have been taken on a bike outing by our hosts and it evokes feelings of camaraderie and biker unity.

We spoke of our general direction of travel and desire to see some of Panama before we rushed to the airport. Helen and Scoop recommended the Caribbean north coast stating that the route across the mountains was beautiful – that’s number one then. Indeed the views of cloud cloaking the mountain tops was spectacular. ‘Presumably you’ll be heading down to the southernmost point on the PanAm in the Darian region before coming back up to Panama City to catch your flight?’ That had never crossed my mind but now seems just as important to us as heading up to Prudhoe Bay to start our trip. Prudhoe Bay is after all, where the Pan American Highway starts so there was never any doubt that we would go there. We’d better see the end of this northern “half” then!

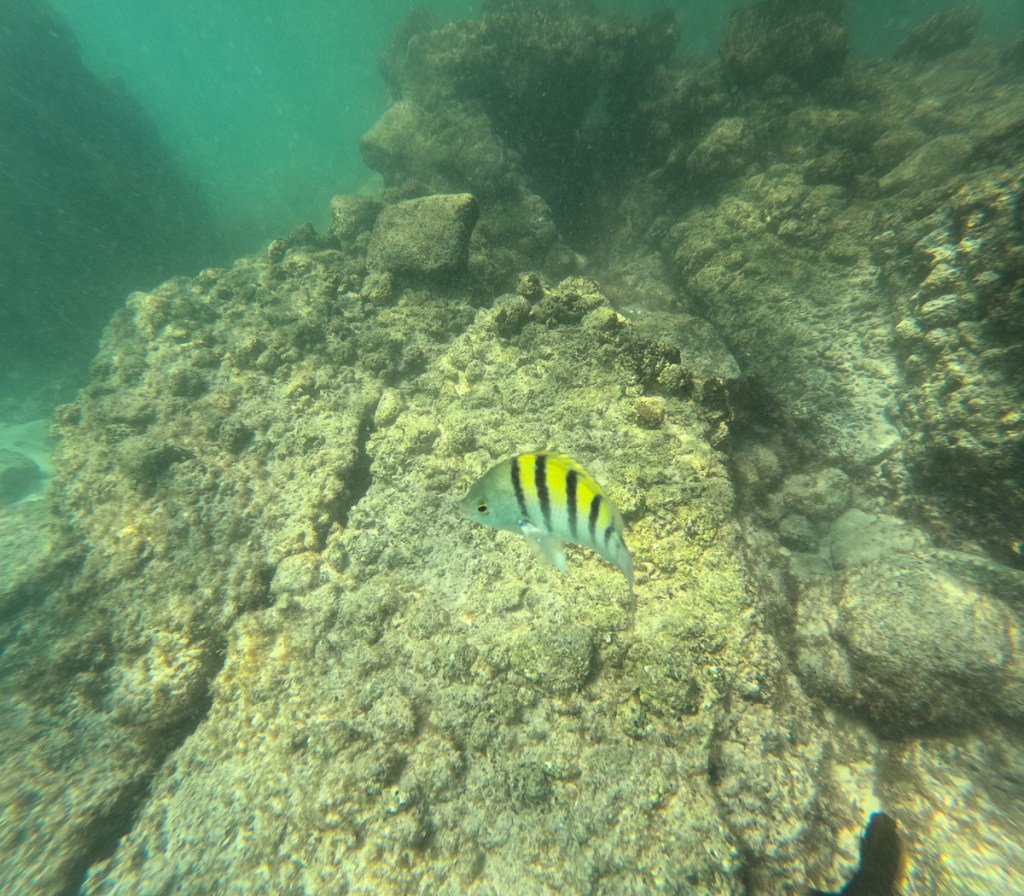

Our highest point on Panama’s northern coast was Almirante. It’s the port where tourists catch the ferry across to the Bocas del Toro archipelago for another dose of tourism laced with the attraction of turtle nesting beaches. The latter was very tempting but we were very happy to avoid more tourism having maxed out in Costa Rica. Sadly, it’s the wrong time of year for the turtles which also influenced our decision. Finding accommodation was our first problem as there wasn’t much online and even less when we tried to check it out down mud lanes barely one car wide. Thankfully a local on a pedal bike led us down one such lane and round the back to find Edgar’s BnB. Edgar spoke very good English and was delightful, encouraging us to go walk-about. It was on our morning ramblings that we came across the dwellings on stilts down by the waters edge. We’d seen houses on stilts, the traditional indigenous dwellings, earlier on our route through the mountains but here they were right up close. Amongst the houses there were modern dug out canoes with flat sterns for the outboard motor. We were fascinated by the area and I tried beating the local kids at skipping – guess what?

Later, down at Calovebora, we saw more of the indigenous life away from the tourist trail. Again, on the Caribbean shore where we saw many traditional dugout canoes of varying sizes and states of repair. The locals were very friendly and mutually intrigued. We ate their pesca y papas fritas (fish & chips), they offered to take us on a motorboat ride. Sadly we declined. I’d have jumped at the chance to have a go in one of their dugouts but that was never on offer and I wasn’t bolshy enough to ask just in case I fell in – amongst the cocodrillos???

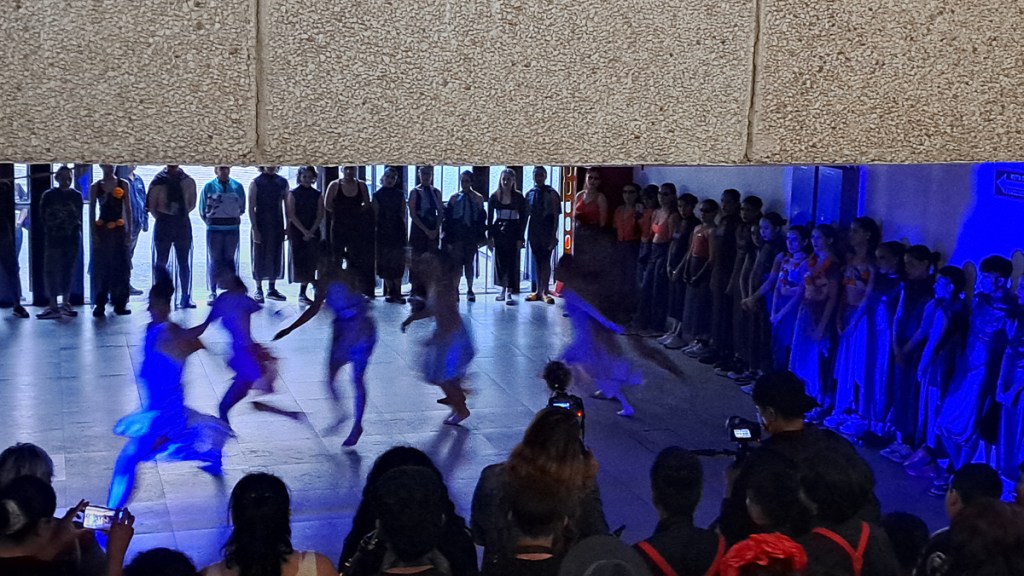

Just by chance we were in the right area to visit to La Ville de Los Santos on the Azuero peninsula at the time of their traditional fair. We had no idea what to expect but soon realised it was a Latin version of our Ardingly South of England Show in the UK. A mix of stalls, souvenirs, eateries, agricultural machinery and livestock but with the added attraction of cowboys. We’d been told on the Thursday that said vaqueros do a tour of the town and indeed we’d seen them off or so we thought. There were maybe 150-200 of them. On our way ‘home’ somewhat later we realised the real scale of the event. It took us two hours to cover the 1.5 kilometres as we sat and watched the hundreds of horses pass by interspersed with beer trucks and free rum top-ups to keep things lubricated. No wonder that there weren’t that many caballeros in the cowboy horse trials the following day.

The Carretera Pan Americana, Highway 1, is the backbone of Panama. We had to use it to reach just about any destination whether it was skipping along the Caribbean coast or the Pacific. There are virtually no parallel minor roads joining the towns, all the roads radiate off the Pan-American. This seems to be the norm along much of Central America’s Caribbean coast where boats are the method of transportation – or gringoes can fly in. But here in Panama it seems almost as difficult to traverse the Pacific coast. On one route Gid was keen to make it across without flogging along the dual carriageway again and came up with some restricted access routes. We’d laughed when the Garmin had stated ‘take the road on the right’ and it was gated farmland. But here he was planning something similar. I vetoed, and he didn’t demur.

It was at about this time that I realised the Garmin seemed to be regularly failing to use excellent roads on obvious routes. It was clear that Panama is actively extending its road network. In the UK I get reminders every so often to update the Garmin maps. I just needed to get round to doing an update and all would be ok. Local guy Darby, who you’ll meet later, had commented that the Garmin navigation is compromised by out of date mapping. I still didn’t think it was a big deal. Then our Open Street Map route into Panama City took us around the Cinta Costera 111 highway – a six laner, plus cycleway, arcing 2km out to sea to bypass the old town and fishing harbour. Garmin’s biker icon was in the water! Highway 111 didn’t look so new. Research showed it opened in 2014. That’s how out of date the 2025 Garmin mapping is! Unfortunately, Panamanian highway engineers are expert at cramming multiple divided highways, with multiple simultaneous slip roads on either or both sides, of the main carriageway, into tight spaces. Garmin was usually oblivious, but Gid’s OSMAnd knew them all but didn’t let on which one we needed. We’d be frantically guessing in a stream of traffic, or stopping on a tiny shoulder so Gid could try to zoom in enough to see the slip-roads and work out what “turn slightly right” actually meant. Very stressful, and a lot of profanity-strewn misroutes.

By luck all our planning, on a bigger scale, had fitted together seamlessly which gave us an extra couple of free days. We took off back down to the Azuero peninsula where we’d seen the fair, but this time aiming for the Pacific coast at the tip. On our return route we more or less by chance ended up at Punta Chame, a sort of peninsula on a peninsula. The road out there was somewhat lumpy and breaking up in places and there weren’t many buildings as we made our way out to the point. It seemed deserted. We found a Swiss cordon bleu chef and ordered the cheapest things on the menu. He explained that it is a kite surfing destination but at this time of year there is no reliable wind. No. Plenty of rain though! He suggested accommodation just up the road but Gid nearly fainted at the price. We were going to give up but decided to take a look at the shipping containers place. We’d stayed in one before and it was alright. This was too with a beautiful view. Beach access, mini swimming pool, what more could we want? We walked out to the tip of the peninsula the following morning when the tide was out. Barely a soul to be seen but the plastic strandline told of the human occupation.

Birds abounded. One, a juvenile yellow headed Caracara, seemed rather needy. Not only did it fail to fly away when I cautiously crept up to take a photo it actually came down to join me. It made some heart wrenching mewing sounds and kept creeping up to peck my toes with its serious looking beak. Sadly we didn’t have any food we could give it. It was gone on our way back so hopefully off to find a tasty lizard or crab.

We packed up the bikes ready for the half-day ride to Panama City – then it started to rain. Rain? No, it utterly pissed down, with thunder and lightning. We hunkered down in our luxury container and waited for the storm to pass. Everything disappeared in a grey mist. Gid went for a trunks-and-barefoot run on the beach once the lightening stopped. It was about this time that Clare’s intercom and Gid’s to-hand bicycle light both stopped working. Clearly a nominal IP67 isn’t equal to Panamanian rain.

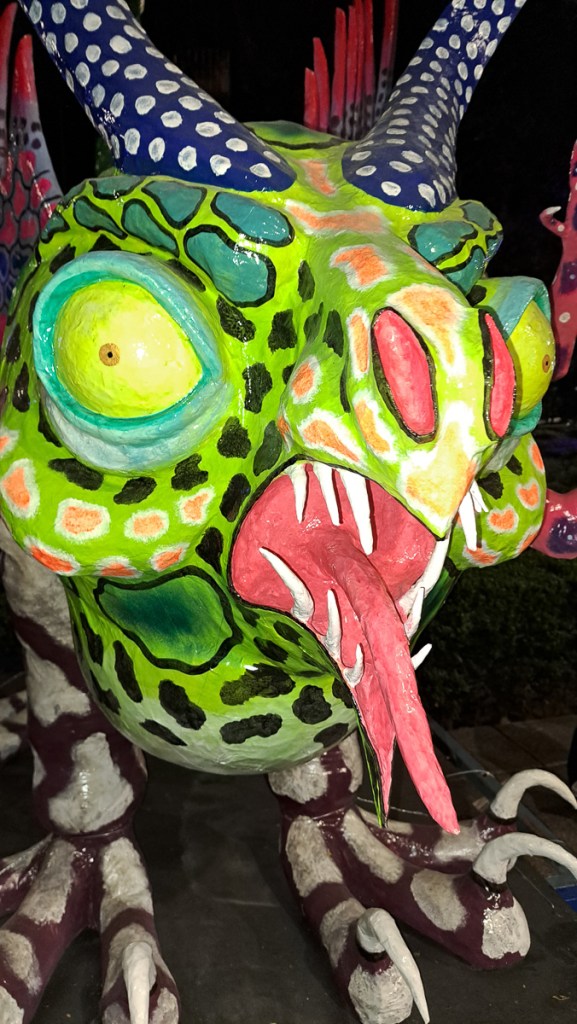

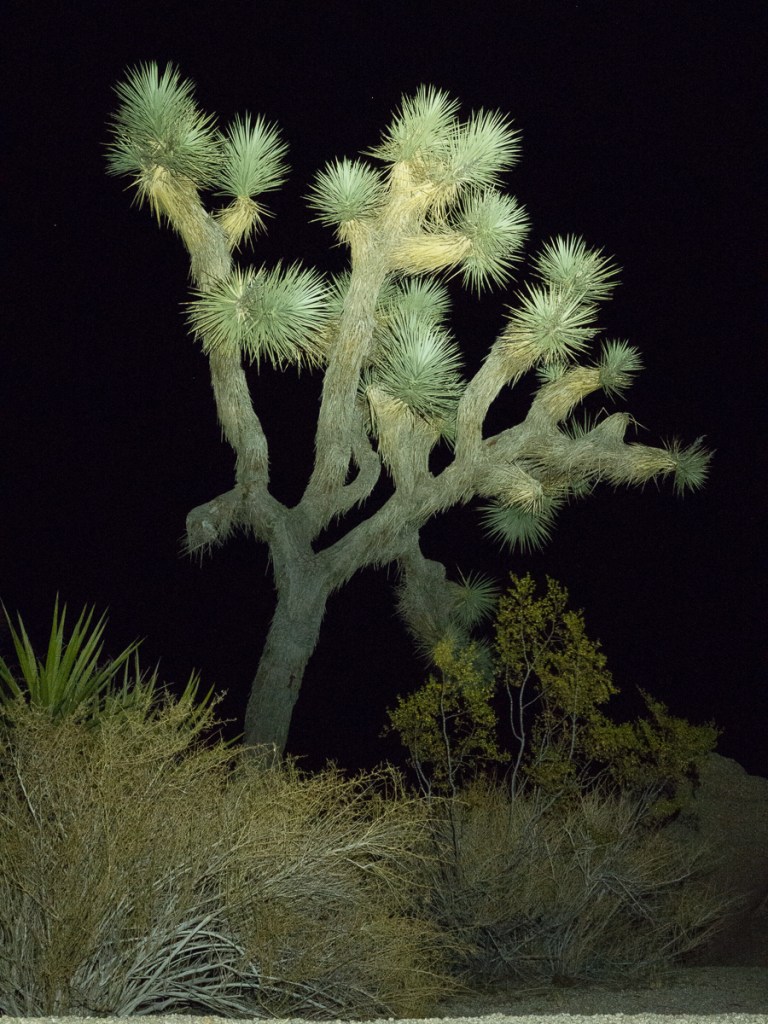

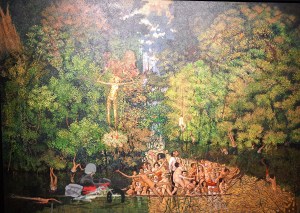

Like pieces of a jigsaw coming together I was getting a better idea of Panama and how it ‘works’. Each new piece of information filled a gap in my understanding of a previous experience. There are six or seven main indigenous peoples in Panama who still practise many of their skills and traditions, protecting their language and way of life. Just outside Panama City we’d visited an Embera village where the tribe is descended from the Embera-Wounaan community down in the Darien area. They are hunter-gatherers who have been allowed to continue living in the rainforest near the capital city. But as it is now a National Park they’re not allowed to hunt. The nations tribespeople are some of the custodians of the rain forests that feed water to the Panama Canal. Outsiders can not readily develop Indian owned land. But they can. During our time in Panama we had had minor but enjoyable interactions with the three groups of indigenous people.

In our first ride into Panama City we’d attempted to get freebie views of the canal. Unlike canals in the UK with towpaths it’s almost all fenced off, along with its roads and services, which are set a good way back. One access was a success but the other attempts ended up down dead-ends, fenced off as part of the “Canal Zone”. One such effort seemed to lead through – private entrances to the sides with an open section and view point at the end. Merrily we arrived just past the parked up coach near the signs stating that crocodiles inhabited the area. No worries, I thought, there’s a long three foot tall barrier right along in front of us. I wasn’t even off my bike before an official arrived in a car. “Trespassing” I thought but no. Crocodiles was the problem. I queried whether they would get over the barrier. The uniformed guy repeated my gesture nodding that, ‘yes, crocodiles come over the barrier.’

Still keen to investigate the canal we visited the official Canal Museum in the city. It was within walking distance from our lodgings but massively biased towards the political story. Three floors of it for the more robust inquisitor. We finally made a trip to the more expensive Mira Flores, the canal side viewing platforms and information centre. Still a bit frustrating for engineer Gid – there’s very little real “how it works” information.

Getting a ship through all the locks takes eight hours but cuts out a three week trip around Cape Horn. It consumes a huge amount of water – viable because of the huge amount of rain the region receives and caches in the rainforest and lakes. In 2016 at Mira Flores, Panama opened larger, modern locks to enable bigger ships to navigate the canal. This latest design conserves 60% of the water making them more water efficient than the old locks which are now over 110 years old. At the visitor centre, a film transposed sepia images of the original steam machinery digging holes, rubble all around, with modern cranes dredging larger loads from a water filled cut. All of our progress is causing its own problems as global climate change is impacting on the region, reducing the rain fall on which the Panama canal is dependent. What does the future hold? Even with the canal Panama is one of the few carbon negative countries in the world, as the 4m population is powered by hydroelectricity, and the rainforest, though depleted, soaks up more CO2 than the humans emit. Most countries have less renewable energy supplies, and nothing like the CO2 sucking rainforest (trees gain bulk maybe 10 times faster than in, say, the UK).

Panana City is like many other cities in Central America and beyond. A complex mix of sky scraper apartment blocks, improvised housing – plastic strips, corrugated iron, cardboard; street sleepers, bare feet, designer trainers, the near naked, beggars, private gyms, plush plazas, derelict sites, shipping container market stores, supermarkets, street vendors, blocked drains, localised floods, three lane highways round the bay. All juxtaposed impacting on each other.

Interestingly, it has relatively few motorcycles – most un-Central-American.

As Clare wrote at the top, Panama City is the conventional place where most PanAm travellers have to surrender their wheels to boat or plane. The PanAm loudly claims to be the world’s longest road, but it mumbles and blushes when anyone mentions “Darien”. For 90km across the Panama/Columbia border, there is no road. Not even an official track. The swampy jungle can be penetrated on foot, ask the smugglers, but even military teams struggle with any kind of vehicle. It’s supposed to be snake and bandit infested too. So like most “travellers”, we will use freight services to skip it.

But to the extent allowed by governments here, and our government’s advice limiting our insurance cover, we tried to get to the end of the road. We had to join, indeed create, an “organized tour”, to visit Panama’s Darien region. We had a jolly two days led by Darby, proprietor of Moto Tour Panama, who would normally prefer to hire you a speedy BMW. I have to say, we envied the F800GS’s headlamp, it seemed to show the road after dark, not a feature of the Himalayan lamps.

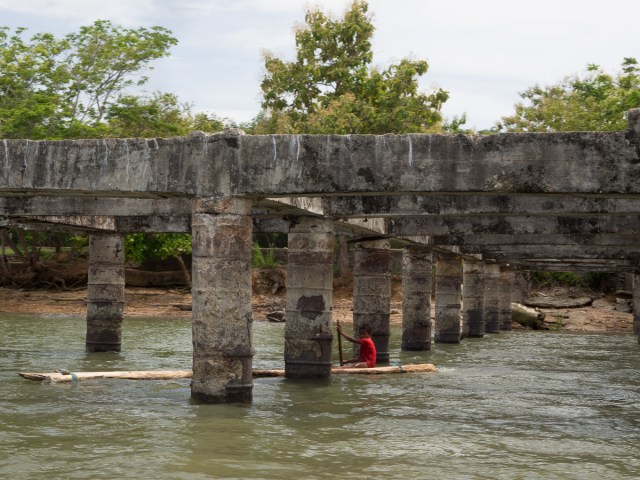

10th May was a big day. We rode into Yaviza, the last town on the PanAm’s northern half. This footbridge is the end. Most of the transport between villages here is by boat, as in the picture. However, in the background you can see a new bridge being built. Maybe soon, you can go a little further.

After this little adventure, we backtracked to Panama City, for a little more tourism and logistics, before freighting the bikes to Colombia… Officially, we’re either halfway, or two thirds, through the trip, depending on if you count in continents or miles or months.