We left Arequipa in Peru heading for the coast. The mechanic at the Royal Enfield dealership suggested that was the way to go. The stark Atacama Desert views were beautiful and the roads winding. But once we descended towards sea level we spotted a flaw in the plan – it became cold and misty, due to the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. By sea level it had cleared. The ride along the coast was dramatic and beautiful with plenty of space to stop for photos.

The route to the border near Tacna was an easy ride with paved roads but we were somewhat confused at the crossing as we had got used to the concept of one, or several buildings, at the leaving end before proceeding a kilometre or two to the entry set of buildings. Here, we ended up visiting three windows in one building and all was done. Gid was concerned that all stages weren’t completed but I pointed out the centre window stamped us into Chile and the bikes out of Peru. It seemed to work.

We only had a short distance to go to reach Arica on the Chilean coast where we intended to stop. As it was still very early, or so we thought, we decided to visit the mummies just up the road from the town stopping for lunch on the way. Out came the phones as always but it took us quite a while to notice we had lost two hours. Rather than three o’clock it was five o’clock and our destination shut at six. Tomorrow then.

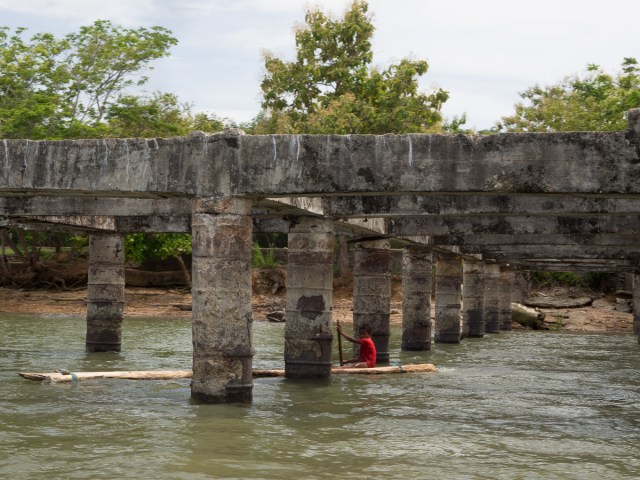

Undeterred by our one day delay we set off towards the mummies taking a more direct route out of town. Spotting some disruption up ahead we proceeded with caution, right up to the tape across the road which blocked the way just before a major bridge rebuild. A truck had just turned off to the right – obviously there was a route through. Having lost sight of the truck we explored the various options on dusty tracks around the old farm buildings before we gave up and headed back. It was twenty minutes or so retracing our steps to the junction that would take us to the mummies museum with no signage indicating the road block anywhere.

It clearly wasn’t going to be our day as arriving at the museum the gates were shut. We hadn’t checked and it didn’t open on Mondays.

Enough was enough. Riding back bypassing Arica we headed south out into the Atacama Desert. We were so pissed off that we hadn’t consider the distance we would be travelling and the implications on fuel. We must have passed several fuel stations but were in no mood for further delays. It wasn’t until we passed a sign that said no fuel for 250 km that alarm bells began to ring. ‘How much fuel have you got?’ I asked Gid. He always runs low first. ‘Providing we take it easy we will probably be ok.’ Probably. Neither of us wanted to turn back and I did have three litres in my jerrycan. Gid had chastised me back in Colombia when at the first fuel stop after our flight, I’d insisted on filling one of my emergency fuel tanks.

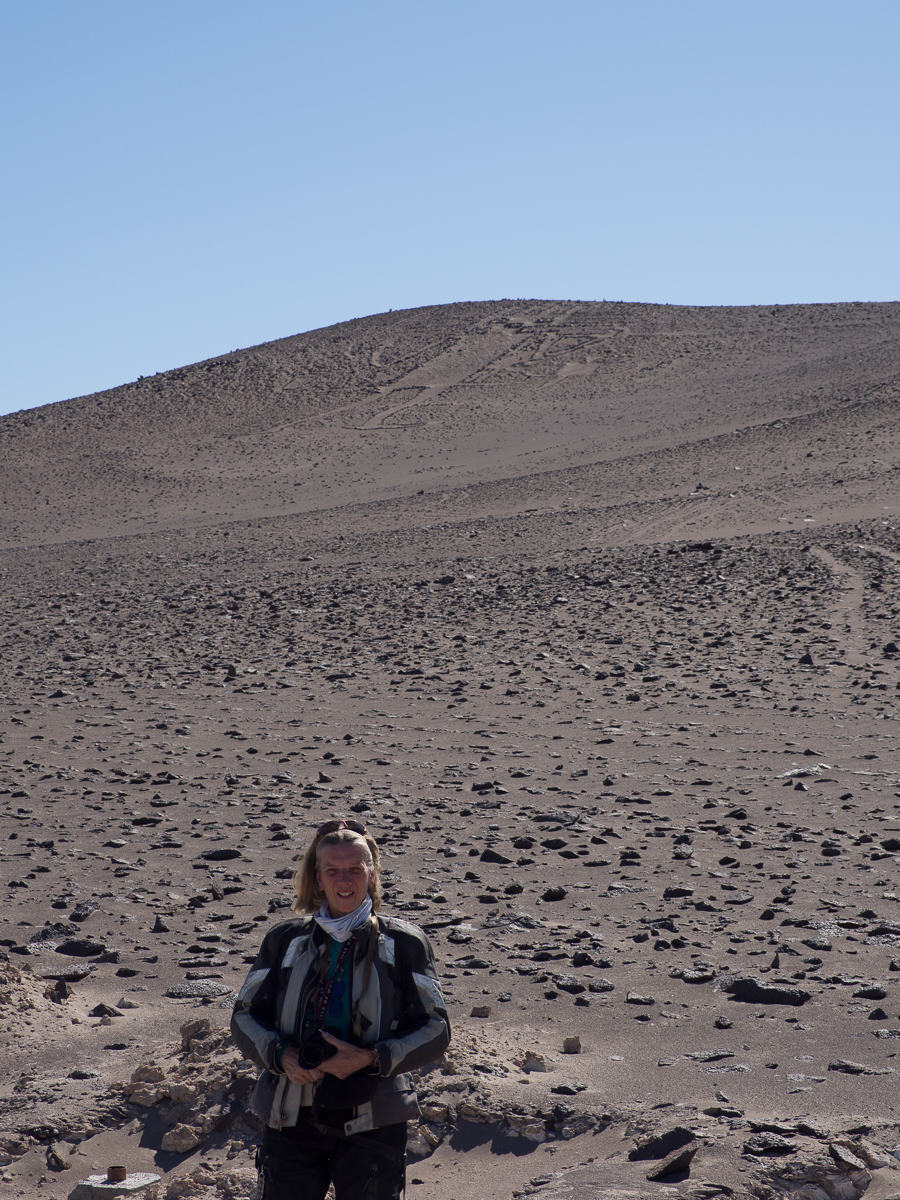

We cruised along tucking in under fifty mph through mile upon mile of barren mountains and valleys. We’d been in the Atacama desert since south Peru first really noticing it around Arequipa and then when we’d been approaching the coast through the mountains. But now in Chile we spent the whole day riding through emptiness with nothing breaking the vast expanse.

We stopped at Huara, the first town since Arica. It offered some accommodation and we hoped fuel. Accommodation yes, fuel no. Given that the hostal owner suggested the content of the available cans could be somewhat questionable we passed on that. The nearest fuel station was still 20-30 km away we were told. Do people in this small town seriously travel 20-30 km to fill the tank. So it would appear!!

The first of our tourist attractions was ten kilometres adjacent to the town. I was keen to see the ancient Gigante de Tarapacá geoglyphs. The largest in the world it was claimed. Gid was reluctant to go on a detour. We crept out to the site stunned at how close 10km looked glancing back with nothing between us and the town.

We made it to Pozo Almonte, creeping all the way but with very little traffic it didn’t matter. With tanks and jerry cans full we sighed with relief as we set off again just over the road to the deserted mining town of Humberstone but fuel had to come first.

Humberstone was fascinating. We whiled away two to three hours peering in the deserted buildings, school house and power station.

It was another day crossing desert before we reached San Pedro de Atacama but here the views took on another dimension. Now the vast emptiness had a backdrop of snow covered mountains. The guanaco (wild llama) the only living thing we saw.

San Pedro de Atacama was a delightful if massively touristy little town surrounded by tourist attractions. We picked the dawn trip to the geysers ‘setting off soon after five and back by eleven’. Sunrise at the geysers was to be the highlight. Our driver, Sergio, had other ideas and did a full tourist trail on our return trip – vicuñas, wild fowl, rhea (Exactly one: “That one’s always there, don’t tell the other guides“, |Sergio said.), flamingos and beautiful views.

Our own trip to see the flamingos at Parque Los Flamencos was also delightful.

There are two mountain passes into Argentina from San Pedro but one we were told was shut with ice on the road. We’d picked an early northern crossing into Argentina in preference to spending the next several days riding down Highway 5 through the Atacama desert, or Highway 1 along the coast. Argentina had a wealth of things to see up in the north and we’d already maxed out on desert. We’d return to Chile later, planning to explore the Carretera Austral before a final push to Ushuaia.

The Paso de Jama was beautiful with snow lining the grassland, vicuñas grazing and the odd goose wading. Up here we were nearer to the snow topped mountains just off the border with Bolivia – another country we’ve seen from afar but not entered.

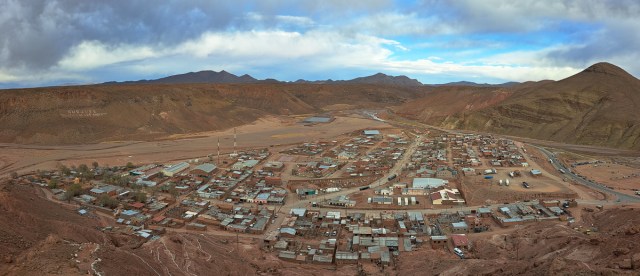

Losing height we dropped down through the mountains into lower land in Argentina. The first town was Susques, a small, dusty place where several river valleys met. From a vantage point up at a shrine behind the town we were amused to see four full sized, if dusty, football pitches in a town barely big enough for one – thus reflecting Argentina’s national commitment to the game. These contrasted with one petrol and one diesel pump in the town. Oh, and one ATM – charging a huge amount of fees for a very small maximum payout.

Ruta 40, a notable adventure riding route in Argentina, peeled away south from the northern end of the town. We had expected some sections to be dirt road but had thought that it would be a high quality – wrong! After two hours having covered 16 miles along washboard, powdery sand sections and loose gravel, with 80 odd miles to go to reach the next junction, we turned back.

On Ruta 52 then 9, heading south we saw mobs of bikers going the other way – all it seemed were Brazilians out for a multi week cruise around. Still losing height we stopped to admire the views little knowing this would be the last time we would be at a scenic viewing spot.

The following day we left San Salvador de Jujuy, heading towards the rural weaving villages. One hour down the road we hit the frequent road works. A contraflow in place with bollards down the middle – a steady progression of traffic. Over the dirt section Gid whinged he was slithering a bit. I hadn’t and I didn’t internalise his warning that it had been sprayed to reduce the rising dust but making it slippery. Leaving the dirt section back onto the surfaced highway wet dust was distributed by the cars into positions two and four as their tyres dropped the mud. We were staggered in positions two and four. I was slightly ahead in four and on reflection, didn’t have enough space to clearly see the road ahead. I had a short lived violent fishtail losing control of the rear wheel and down I went.

After all the back-of-beyond places, dirt roads, severe poverty and lacking facilities, it had to happen here. On a main road near cities, in one of the most developed countries we’ve been in. Roadworks management were there in a flash. Traffic didn’t try and drive over us. Someone called an ambulance and the police. Gid, who’d deliberately dropped his bike on the opposite verge, was confused by a lady who knelt to help, and took Clare’s hand. Was she a nurse? No, she was praying – hard.

A bruised knee, chipped rib and broken collarbone. It could have been a lot worse but that is the end of our trip.

We gallantly considered our options for making it down to Ushuaia, our target destination. We’re in the correct – the ultimate – country just at the wrong end. My moments of positive thinking weren’t in touch with reality. Our trip had to end in late November so time was running out, we had to dispose of our bikes in a country where it’s illegal for us to sell them, no mean feat. On top of that it soon became quite clear that I needed recovery time. I wasn’t going to manage being stuffed into a car and joggled for hour upon hour along over endless speed bumps, potholes, road works and metal studs.

We stopped for the best part of two weeks in the perfectly comfortable little hotel Gid had found a block from the hospital in Perico. I was groaning with frustration at staying still and at my general feebleness. Gid was desperately trying to find a safe, bearable for Clare, and not insanely expensive, way of moving the bikes and digging us out. Short of time, he only managed to advertise them for a week or so before concluding that the only reliable option was the fabulously expensive, wasteful, and CO2-emitting route of trucking them to Buenos Aires and shipping them home, while we flew to BA, stopped a week, and then followed. A sad end to our fabulous adventure. Be nice to see the grandchildren again. Will we come back?